This post is part of a series on informality in practice, to be published at regular interval on the ATS blog.

n.3

FANTASIA PAULISTA

Or: building citizens, one brick at the time

Brazil is a country with a violent past – a Wild-West kind of violence.

Take Maria da Conceição Pereira Silva, for example. Born in 1945 in Afogados de Sertania, deep in the Brazilian Nordeste, one of her first memories was seeing a bunch of jagunços, thugs with guns, beating her father on behalf of the local fazendeiro.

Her uncle Carlos, whose name was always mentioned with a mix of respect and disapproval by family members, had been a member of Lampião’s gang – and had been hanged with him in 1938 in Alagoas. The country had been an open frontier for so many years, and cangaceiros such as Lampião or Carlos, were like Jesse James, free men of the Wild West that robbed the rich to give the poor.

Then at some point, Brazil’s frontier turned outside in, so to speak: the place where you would go to build something for yourself was not the countryside anymore, but Brazil’s big cities.

And Maria was no exception: on the 25 of August 1954 she was sitting on the back of a truck with two of her older brothers, staring in the bright morning light to the flat farmland as she was leaving of the Brazilian Nordeste, headed to São Paulo. She remember her brothers talking about the President, who had apparently just shot himself – and discussing the best ways to take one’s life. She wandered why a President would kill himself, while all the derelict farmers of Afogados de Sertania seemed to be rather attached to their own miserable life.

Two weeks and 2,500 kilometers later, she set foot in the burgeoning metropolis.

When I got here I didn’t understand the hard poetry of your street corners… And you were a difficult beginning… And those who had dreamed of a happy city, soon learn to call you reality… From the people oppressed in the waiting lines, in the shanty towns, from the power of the money, which rises and destroys beauty, from the ugly smoke that clouds the sky, erasing the stars – from all that your urban poets are born, your forest factories, your rain gods… And the immigrant walks in your drizzle, and marvels at how pretty you are…

Caetano Veloso | Sampa, from the album Muito (Dentro da Estrela Azulada) [1978], inaccurate translation.

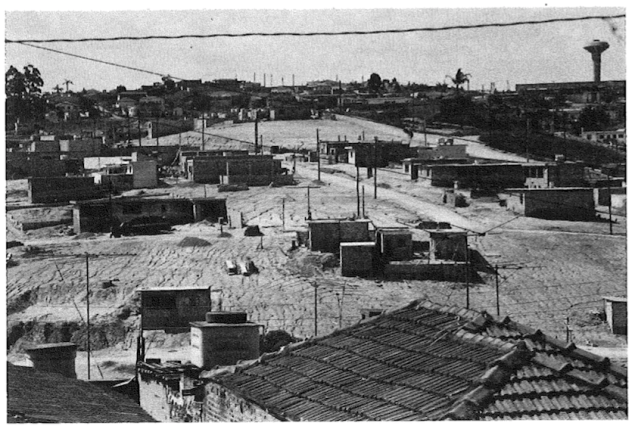

In the 1950s São Paulo was the epicentre of a massive process of urbanization: hundreds of thousands Brazilians were on the move, from the poor countryside to the peripheries of the big cities. In the following thirty years, this process completely changed the social and economic fabric of the country, transforming the rural Brazil of the 1940s into a predominantly urban, industrialized country – and São Paulo into one of the world’s largest metropolises.

Deprived of the benefit of the hindsight, and relatively uninterested in the field of urban history, in 1956 Maria could only notice some of the annoying features of that situation.

As for many of her fellow rural immigrants, her first stop in São Paulo was in the relatively central industrial neighbourhoods, where she and her brothers hoped to find some work. And work did they find – all the rest seemed to lacking, though.

More precisely, a city for them seems nowhere to be found.

Soon enough, Maria began a centripetal journey of several years, as raising rents and unforgiving landlords pushed her toward the urban margins, where streets were dirt roads, and houses were barracos, shacks; where local gangs preyed on the residents, but nobody would call the cops because they were sometime much worse.

Maria realized that the city seemed to grow under her feet: she would settle in a slum, and after a while dirt roads were paved, rents would go up, or the police would come and chase away the residents – and the journey would start over again.

Only thing, life did not just reboot at every stop: at some point Maria found a good man, Roberto, and marry, and had a son, João – and grew tired of this nomadic life.

Then one day something happened that changed Maria’s life forever.

[It was on April 11, 1964 – Maria remembers the date because it was the day that general became President after that other guy, Jango, left the country for Uruguay – Maria kinda liked the old guy more than the new general (she would not trust a rich man from the Norteste), but she was agnostic as politics was concerned – and what any President had ever done for her anyway?]

That day Roberto came home with a piece of paper in his hands – a deed of property for a piece of land, a building plot in a place named Jardim das Camélias.

In a few weeks a barraco was built on the plot – a small tin house that Roberto, a construction worker, would incessantly expand and improve during the next years, also to accommodate two more kids, José e Joaquim.

To be sure, most of Maria’s life remained the same: dirt roads and shacks, open-air sewage, etc. – and an interminable, four hours commute to work. But Maria finally had her casa própria: she had become a homeowner.

Or so she though: turned out that the guy that had sold the deed of property to Roberto was not the owner of the land in the first place. Maria and Roberto learned that when an official from the court showed up with an order of eviction for them and a bunch of other residents.

And for a moment Maria thought that she had never left Lampião’s Norteste.

As the news run through the neighbourhood, a many people gathered outside the house; the official found himself surrounded by an angry crowd; his papers were scattered all over the muddy street, and he was beaten out of the neighbourhood. He came back later with the cops, who beat the people and made a few arrests, which turned into a small-scale riot around the local police station, which brought more arrests. The residents formed an association to fight eviction, and hired a lawyer to follow their case, but after a few weeks their the guy was shot and killed – word on the street was that the developers had done it.

But Maria did not move: this is not fucking Norteste, she though; she was working, and paying taxes… porra, she was even taking evening classes to learn to read! And most of all, she had bought a house with good money, and so she owned it – she had earned her place in São Paulo.

And São Paulo, for the first time, seemed to be forthcoming.

The metropolis continued its expansion: new roads were paved, new utility poles were planted, and sewage pipes were installed, as tin and wood turned into bricks and mortar. As always, the city was busy pushing toward its expanding margins, but this time Maria had an anchor in the form of her house. By the end of 1970s she was living in the city rather than on its margins; and in a real house rather than a barraco.

And she was not alone. Maria did not care much about politics, and certainly did not trust politicians. Yes, Roberto, now a steelworker, had participated in the great strikes of 1978-1980. And this new Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) was ok – a bunch of communists, Maria thought, but you had to give them credit for showing some genuine interest for the neighbourhood; and she liked that Lula guy, a nordestino like her, from Caetes.

But what really meant something for Maria was the neighbourhood: politicians talked about “politics”, “democracy”, “reforms” – like most men like to do. Maria and her girlfriends were interested in their own houses – a habitação é mulher, she always said, the house is a woman’s thing. They needed a place to leave their kids while they were at work, and local schools where the children could learn to read, and math, so they would not be fooled at their first paycheck. They needed better buses, the sewage was still a big problem, and sometime it would take ages before someone would come to the neighbourhood to pick up the trash.

And guess what? The neighbourhood itself took care of all this more than any politician would do: the residents worked to improve their houses, and paid for the lawyer’s bill; they even paid for the rent of the PT’s local office – that’s was one of Maria’s favourite lines when Roberto, a regular in the meetings at the local PT chapter, was talking nonsense: “we are helping the PT much more than the PT is helping us”.

And most of all, the neighbourhood existed, and had become pretty, because of what they did, not the PT: every new road, bus line, or second storey was the product of the stubbornness of the residents, and a testament to their achievements in life.

[FLASHFORWARD]

On October 27, 2002, Maria was in a big square full of people – all her family was there (Maria was a grandma now), along with many other familiar faces from Jardim das Camélias. That was a big night for everybody, because Lula finally made it: more than fifteen years after the generals had gone, at his fourth attempt, he had been elected President.

An overexcited and drunk Carlos was busy, half talking, half weeping with his friends about hope, about a bright future, about the first left-wing President since Goulart… But Maria knew better: the thing was not about the future, but about the past. A nordestino from São Paulo’s peripheries had just become President – and that meant that all of them had made it.

They had started from the margins – and brick by brick they had built a new city for them, and a new country.

October 27th, 2002 – Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva elected President of Brasil.

Now, what’s the moral from Maria’s story?

Well, if you agree with James Holston (whose great 2008 book, Insurgent Citizenship, has inspired this post – or better dictated it), the key point is the following: Brazil’s transition to democracy, epitomized by Lula’s election in 2002, is the product of a process of urbanization that transformed the country and created new forms of citizenship.

At the centre of this process there is the practice of autoconstrução (self-building), through which – day by day, brick by brick – the marginalized immigrant population created it own city, or more precisely, a city that was adapted to their needs.

These practices were quite removed from a conventional understanding of politics: home ownership, property conflict, urban services, child care, education, environmental hazards, “issues historically marginal to the traditional political arenas of men, work unions, the state, and political parties, but ones that have in fact been more effective in mobilizing working-class Brazilian to fight for citizenship rights and to develop new cultural identities and sensibilities of self” (Holston 2008: 156).

However removed from “politics” in the conventional sense, the cumulative nature of these practices produced results on a grand scale: through everyday routines and activities the residents of the many Jardims das Camélias of Brazil came to challenge the self-evident, “natural” legitimacy of hegemonic power – that’s what Holston calls “insurgent citizenship”.

[THE SAD POST SCRIPTUM]

James Holston wrote it in 2008: “precisely as democracy has taken root [in Brazil], new kinds of violence, injustice, corruption, and impunity have increased dramatically” (Holston 2008: 271), so for the second time in a row there’s no happy ending here: on October 28, 2018, Maria’s back was giving her the usual pain – but she made an effort to go out and vote for Jair Bolsonaro, the right-wing candidate to presidential elections who had said he liked the old dictatorship.

She had not really changed her politics – she would vehemently deny she ever had one – but she’s was sick and tired of the PT; she never really liked Dilma (the daughter of a lawyer, she was never one of us, she thought) and could not stand all those vagabundos – selling drugs, shooting each other all the time, bothering good citizens like her.

Few weeks ago she heard the tv announcing that last year Brazil had broken its all-time record for homicides; Bolsonaro said the police is going to matar mais vagabundos, kill more thugs – fine for me, thought Maria: in life, you reap what you sow.

Roberto had still voted for the PT, and would not talk to her for days, she knew that – but he was wrong. And São Paulo was right, as always: Bolsonaro got there more votes that anyone else in history.

Criolo | Não Existe Amor em SP [There’s no love in São Paulo], from the album Nó na Orelha [2011]

————————–

Marco Allegra is postdoctoral researcher at ICS-ULisboa.

Thanks to Emerson Roberto de Araújo Pessoa for the music and more.

**

Did you like the post? Didn’t you? Anything you want to share? Got better links and references than ours? Send us a comment through the form below. The series is open to contributions which roughly follow our guidelines – for more information please contact us at informalityinpractice@gmail.com

I think if the reader is someone who does not know the formation of urban Brazil, if he is a beginner in “brasilidades”, the text does a good job.

However, even considering the space for the text and rhythm of the narrative, there are some socio-historical aspects in the formation of the Brazilian urban peripheries that would need more precision. About the political-electoral aspects, especially on the last presidential election, there are also more nuances than it may seem. Finally, I disagree with Holston’s analysis of the rise in “violence, injustice, corruption, and impunity” in democratic Brazil. All of the numbers regarding quality of life and social inequality have improved greatly in the democratic period compared with the dictatorial regime. With the exception of homicides, of course. However, it should be noted that in the dictatorial period, some criminal practices and violent institutions that are now rooted in our cities have originated or began to control territories in peripheral urban environments: gangs of illicit drug traffickers, extermination groups of deviants or local political leaders, control of territories and local politics in peripheral neighborhoods by families linked to illegal gambling (“jogo do bicho”), extremely violent and corrupt military police, international trafficking in marijuana and cocaine with the participation of state agents. It is also to be considered that in the dictatorial period there was no reliable public data nor a free press with wide visibility, as it is today.

As a suggestion for the debate on informal practices of city construction in Brazil, I suggest the works of Maurício de Abreu (ex. “A Evolução Urbana do Rio de Janeiro”), the works of Michel Agier (ex. “Antropologia da Cidade”), recent works by Vera Telles, Daniel Hirata and Gabriel Feltran about “illegalismos” in São Paulo, and works that talk about “mutirão”, this category of indigenous origin of self-construction based on collective work, fundamental for the construction of the ceiling and structures of concrete in many Brazilian houses, such as mine.

A hug for you and your team, Marco!

GostarGostar