By: Kaya Schwemmlein

(…) there is no relationship of power without its corresponding constitution of a field of knowledge, no relationship of knowledge that doesn’t imply and constitute at the same time relationships of power” (Foucault, 1978)

Agriculture in Europe, as a practice and a field of knowledge, has been inextricably linked to the concept of development used in Western society since the Industrial Revolution (late 18th and 19th centuries). Historically speaking, the process of development has its roots in a patriarchal project that claims to satisfy society’s needs and achieve constant progress by commodification of commons, by accumulation of capital and by increase of private ownership, profits and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (e.g., Watson, 2004; Shiva, 1988). Development in the agricultural sector, then, translates into a constant demand for space, resources and capital for a steady production and accumulation of food that systematically demands the privatization of a vast number of common resources (i.e., seeds and water) and demands a constant flow of cheap labor and “available” land (e.g., Nolte et al., 2016, Holt-Giménez, 2017).

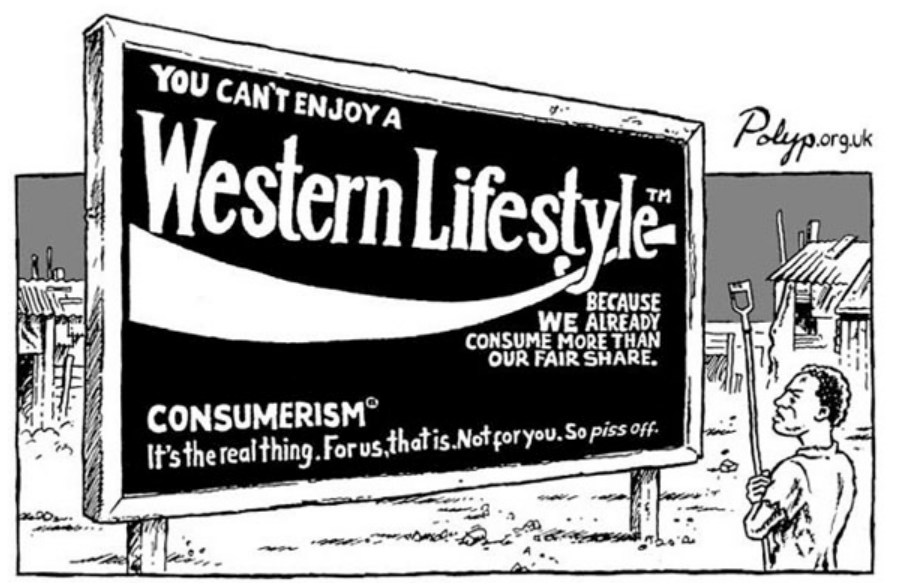

As the reinvigorated global “land rush” demonstrates, the Western hegemonic food production paradigm built on the premises of perpetual growth is still alive and well, to the point in which it has been associated to the expansions of large-scale monocultures for food production equated to a previous era of plantation economies.

Figure 1. Western Lifestyle. Source: Polyp, with authorization of the author.

The current European agrarian sector the setting of a hegemonic cluster of ways of doing and knowing can be seen at several levels:

- At the political level, as in the requirements set out by the European Agenda 2030, with the key components being the “Food to Fork Strategy” alongside the “Biodiversity Strategy”, or in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which set a hegemonic notion for development of society and a preferred pathway to achieve it;

- At the economic level, by establishing new frameworks, as in the green economy, and/or by a constant economic framing of food policy through trade agreements such as the SPS (The World Trade Organization’s Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures);

- At the institutional level, by the exponential growth of scientific production and know-how related to values such as efficiency, productivity-boosting, and attempting at climate change resistance and resilience only through an increased use of technologies, i.e. biotechnologies and genetic-engineering.

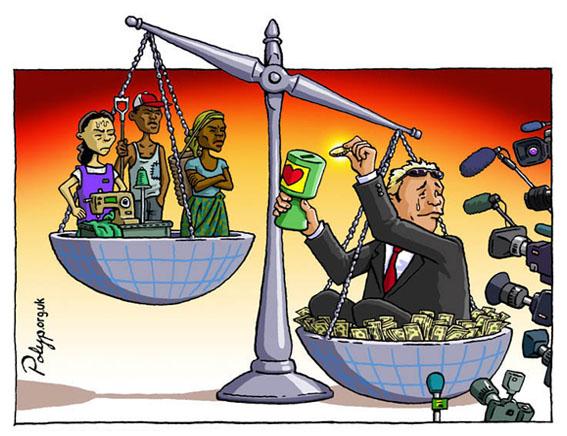

Even if the current geopolitical situation – from the COVID-19 pandemic to the escalating war between Russia and Ukraine – has exposed the weaknesses of the global capitalist market supply, it can be said that a vivid process of silencing and marginalization of subaltern workers in the agricultural sector is still systematically occurring – as in the case of women, small-scale farmers, fisher-folk, shepherds, immigrants that work the fields. This process juxtaposes and intertwines with the devaluation of local knowledge, exclusion from common natural resources and the struggle of said workers to attain fundamental human rights.

If there is an idea I would like to convey with my argument is that there seems to be no ethical and sustainable way of life without a change in power relations. More specifically, I argue that what we are dealing with here is undoubtedly an exercise of biopower. According to Michel Foucault’s definition (Foucault 1978), biopower is a type of relationship of power in which the life of the individuals involved is at stake, both in the form of the single subject in its relation with their body, and in the form of an overall regulation of the body of society, the body qua species. Biopower is on the one side discipline (anatomo-politics of the individual), individualizing objectification of the subjectivities; on the other, regulation (bio-politics of the populations), processes of systematic normalization of people’s attitudes towards health, sex, etc. What is, after all, the proposed green transition process linked to the “Green Deal” if not an exercise in the government of people’s lives? Indeed, and more generally speaking, it is a matter of governance/government, always in a Foucauldian sense, insofar as it is the conduct of one’s conduct and it involves the strategic disposition of an attempt at structuring the field of possible actions among a given set of actors (Foucault, 1982). This modus operandi is not new, as it has happened many times before in the agricultural sector. One of the most prominent examples is the political reorganization process linked to the Green Revolution: “(…) the processes of state reconfiguration, capitalist accumulation, concentration of power, disenfranchisement, agricultural investment and innovation (…)” (Raj Patel, 2012).

As a first step, to attain sustainable, healthy and fair food systems, European policy design should no longer disregard historical processes that generated hegemonic power relations, such as colonialism, racism, neoliberalism, and capitalism. Neither should it ignore the implications of today’s global land rush dynamics associated with intensive farming practices linked to human rights violations, resource exhaustion, and desertification processes.

In this sense, an urgent political priority is to understand how to rebalance power relations, by giving power to those who work the land and make pluralistic peasants’ voices heard. Let them lead the dialogue on concrete solutions for climate change. Give them a platform. Let them actively participate in policy formulation.

I believe that climate change and the pathway to sustainable agriculture should be based on peasant-led agriculture and principles of food sovereignty; in other words, a comprehensive model for transforming food systems (LVC, 2020) and to halt further corporate grab of land, resources, and ultimately, lives.

Kaya Schwemmlein is a PhD student at ICS-ULisboa in the Doctoral Program in Climate Change and Sustainable Development Policies. She is currently working on sustainable agrifood systems and socio-ecological development from the perspective of the water-energy-food nexus. kaya.schwemmlein@ics.ulisboa.pt