By: Olivia Bina

Premise

The rapidly multiplying and intensifying socio-ecological-economic crises are merging into a polycrisis: ‘a single, macro-crisis of interconnected, runaway failures of Earth’s vital natural and social systems that irreversibly degrades humanity’s prospects’ (Homer-Dixon et al.). As a result, new questions are finally being asked in more and more arenas related to shaping the present and future of urbanisation across the world: What if biodiversity, climate and equality were the core global priorities? What if all life mattered? What if we recognised that we co-exist and share the space in our cities with other-than-human species?

Underlying these questions is the need to renegotiate human-nature relationships and the paradigms that underpin them. Despite the crises, there is also a reminder that our planet is uniquely gifted with life, and largely thanks to the contribution of plants, capable of ensuring the conditions for life (Gaia hypothesis); and we are witnessing a widening fracture in centuries of (epistemic) assumptions, belief systems, and worldviews that have dominated our understanding of reality when it comes to ‘humans and nature’. Today we are witnessing a radical change: millennia of wisdom traditions, decades of critical scholarship, and years of policy-making are converging to call for an end to the very real -yet ultimately false- dichotomy of ‘humans-nature’ (also discussed as culture-nature, society-nature). From this, we argue it is a small but essential step to question the separation between the built environment and nature.

Few arenas illustrate this struggle as powerfully as that of the built environment. The rising attention towards “renaturing” cities, and the demand for new, positive visions of urban futures that usher in a new human-nature and built environment-nature relationship are just examples of innovative perspectives flourishing through the fractures of dominant modes of making cities.

From what nature can do for cities…

Over the last two centuries, cities have been increasingly designed to respond to economic goals, efficiency priorities, and human needs creating a separation between human spaces and the natural world. Originally, cities grew more organically with their natural environment, but this was gradually lost with the rise of modernity’s nature-human divide. This separation has increasingly affected the way we think about urban form and how we design urban spaces, leading to a prevalence of ‘grey infrastructure’ and a certain homogeneity. This has come at the expense of spaces capable of supporting a diversity of life (vegetal, human and all other animals above and within our soils) in urban areas.

There is a growing need to challenge the dominant economic-efficient-human-centric viewpoint of the urban form. Even more so, in an era where climate change and environmental degradation are pressing concerns, the consequences of such nature-human separation are being experienced in terms of urban health, wellbeing, and even survival.

Much of the growing attention to human-nature relationships in cities is driven by the growing impacts, damage, and risks arising from climate change and (less visible to urbanites) biodiversity collapse. Nature-based solutions (NBS) have emerged as the leading policy response to the urban heat island (UHI) flooding, pollution, and drought conditions. Urban trees, urban forests, and green spaces are all called upon to help redress the damage and prevent existential risks from expanding. NBSs are critical for addressing human needs for security and well-being. Yet, the renegotiation of human-nature relationships goes beyond the utilitarian “nature for society” paradigm, where we make the most of ecosystem services to solve the polycrisis. NBSs continue to prioritise economic goals, efficiency, and human needs, often reinforcing the separation between humans and nature. This approach can encourage us to use the latter as a way to solve human-made problems: for example, reducing trees to ‘air-conditioning technology’, or ‘carbon sticks’.

… To what cities can change to be part of Life

This is not only a matter of what values we assign to nature and more-than-human life, but also raises broader questions about how we see ourselves as part of this living planet. It prompts us to consider how this might influence the way we think about the urban form and our approach to the design of urban spaces in the future. There is some progress making its way through the fractures of dominant modes of citymaking: the quest for “renaturing” cities and the demand for new, positive visions of urban futures that might usher a new human-built environment-nature relationships. However, we need much more: bold, generous visions of the urban form beyond human-centred perspectives. This is precisely what we set out to contribute to by launching a worldwide crowd-sourcing experiment: ‘FORM FOLLOWS LIFE REINVENTING CITIES’.

The aim is to build on the insights arising from this rapidly expanding corpus by inquiring into the potential of focusing on the importance of all life forms. This goes beyond nature-based solution(ism), or ideas of urban rewilding, or renaturing. A perspective that views all existence as relational, where humans are not separate from the natural world but are an integral part of it. It emphasises a responsibility to care for all animate and inanimate forms within this interconnected web of life. The hope is that such interpretative lens contributes to seed more radically positive stories about urban futures, inviting an integrative worldview that might undo the basic ontology of separateness dominating cities.

The ‘FORM FOLLOWS LIFE REINVENTING CITIES’ competition aims to challenge participants to reimagine urban spaces from the perspective of nature, understood here as encompassing all forms of life (human and more-than-human), and their relational qualities and needs. By “Life’s relationality” we want to refer to the interconnectedness and interdependence of all living things within the urban landscape. By this notion, we wish to emphasise the idea that life doesn’t exist in isolation but rather thrives through a network of complex relationships. We suggest that understanding, respecting, and enabling life’s web of relationships through better design is vital for promoting bioculturally diverse, healthy, and thriving cities in the 21st century.

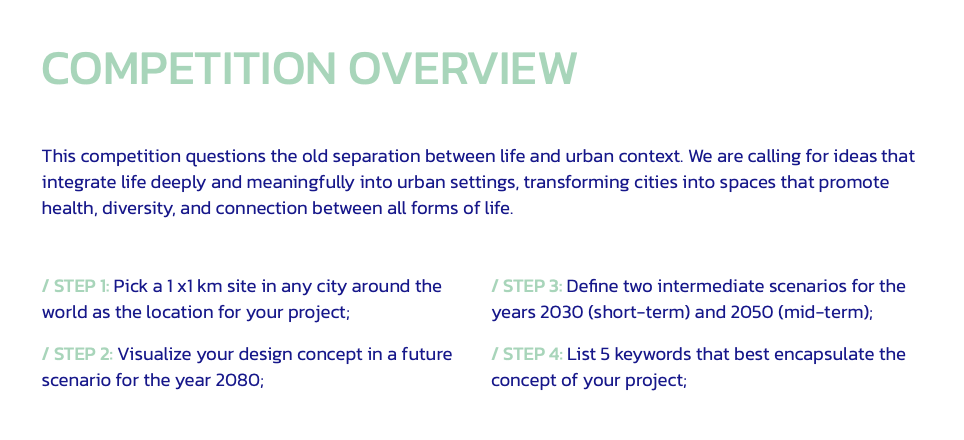

Methodologically, we build on the device of a ‘thought experiment’ and grounded theory: ‘a test in which one imagines the practical outcome of a hypothesis when physical proof may not be available’. To challenge the dominant economic-efficient-human-centric viewpoint shaping cities, we invite members from the communities of architects, landscape architects, designers, and urban planners (globally) to complete the following imaginary journey:

- from “form follows function” (principle of design associated with late 19th– and early 20th – Louis Sullivan – centuries architecture and industrial design);

- through “form follows systems” (principle linking to socio-ecological systems – Wong Mun Sum);

- towards “form follows life” (principle inviting form to promote and enhance life’s web of relationships, interdependence, and mutual thriving – Olivia Bina inspired by the work of Gilles Clément and Patrick Geddes).

And to do so by signing up to the worldwide digital competition ‘FORM FOLLOWS LIFE REINVENTING CITIES’, curated by myself, Josefine Fokdal and the Non-A team. The approach is designed to offer space for creative exploration of what it might entail to decenter the human and weave together new, hopeful, caring, emancipatory fabrics of urban form into the future.

An international jury will be assessing the entries of 50 finalists, with winners expected to be announced by 30th September, 2024. We will be publishing the best entries in an edited book and will be building on this experience to design a research project that explores the theme of “Form follows Life” in greater inter- and trans-disciplinary detail.

Olivia Bina is Senior Researcher at the Institute of Social Sciences University of Lisbon, Fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science. Her research focuses on transformative change for sustainable urban futures, on the critique of “green” growth and notions of scarcity, and on exploring the unlimited potential of human-nature connectedness.