By: Nicoletta Moschini

“From beasts we scorn as soulless,

in forest, field and den,

the cry goes up to witness

the soullessness of men.”

M. Frida Hartley

We are all eyewitnesses to a dystopian historical period in which there are more overweight than undernourished people. We prefer to consume water in plastic bottles rather than tap water. Entire geographic areas of Europe, especially southern Portugal, Italy, and Spain, are at high risk of desertification, and globally, 2 billion people have difficult access to safe water sources. Yet, the global average water footprint to produce 1 kilogram of beef is 15,415 liters, meaning 2,400 liters to make a single hamburger – the equivalent of about 3 months of showers. Worldwide, 900 million people are in a state of severe food insecurity. Yet, the world’s cattle require an amount of calories equivalent to the caloric needs of 8.7 billion humans. Moreover, our Planet’s habitable land is mainly used for agriculture, with nearly 80% of farmland linked to meat and dairy production. Yet, livestock produces less than 20% of the world’s supply of calories.

Figure 1. Global land use for food production, OurWorldInData.org, 2019.

We are in the midst of a sixth mass extinction triggered by humans over the last 200 years. The dinosaurs survived one of the five great mass extinctions and subsequently dominated and thrived on the Planet for more than 150 million years. Unlike us, who have become the most critical driver of change, biologically, geologically, and atmospherically, so much so that we have named this new Earth Age the Anthropocene. If we don’t take action, we will also simultaneously go down in history as the promoter and culprit of the shortest Earth Age ever.

Unlike the dinosaurs, however, we can intervene; we have the technological, cultural, and scientific tools to turn things around. We are not mere observers, as we like to think so often – somewhat to limit the scope of our responsibilities; somewhat because in the age of too much choice, too much consumption, and too many possibilities, we are more frozen in the face of such vast scenarios of meaning, which often escape us, than heartened.

It is no longer the right to vote that defines us as citizens; rather, we define ourselves and are defined by our consumption choices. Before anything else, we are consumers of goods, services, and feelings. As such, our power is made explicit whenever we purchase something.

While it is true that there are choices that we would like to be able to act on, but for which we do not yet have the tools (purchasing an electric car; being able to go to work and school with the sole use of efficient and punctual public transportation; limiting water loss due to old and inefficient infrastructure), there is one that would give us the possibility of being promoters of choices with a lower environmental impact: what we put on our plates three times a day.

We have now universally acknowledged that smoking is dangerous for our health, that plastic should be recycled, and even in Europe, with a robust wine industry, Ireland has gone so far as to recognize all alcohol products as carcinogenic. Yet, when we talk about food and its impact on our Planet, namely animal-based foods, the dialogue seems to stop and close in an insuperable dichotomy. In fact, there is nowadays a tendency to polarise discourses and perspectives. In this heated scenario, vegans are considered extremists, while omnivores are the true and only holders of the “natural and traditional diet” order. This dichotomy annihilates any chance to meet halfway, to recognize, and to understand new ideas. Personal, cultural, and religious connotations take over.

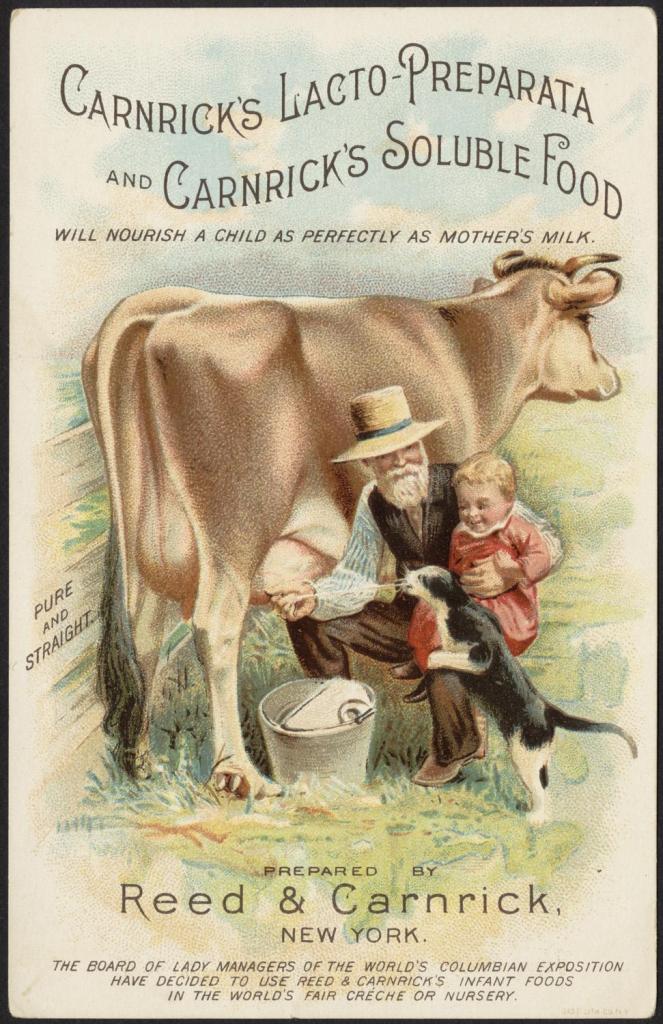

These stereotypes result from misinformation and decades of brilliant marketing campaigns that have given us the image of a happy cow cuddled by the farmer in a straw hat as she is milked to ensure we get not so much the milk but the calcium we need. So these animals, legally defined as livestock, become, in our eyes, mere products over which we claim property rights. The survival of our species is at stake, after all.

We used to hunt; I am often reminded. That is correct; it is a fact we can easily document historically. I like to answer that at one time, to play the “what we used to do” game, we also burned women because we thought they were witches. The conquerors were worth more than the conquered, and this narrative allowed us to justify centuries of slavery and millions of deaths. Women had no right to vote or access public life because they were considered inferior and unstable beings, the exclusive property of the pater familias. Until forty years ago in Italy, we had the “rehabilitating marriage”: a woman victim of sexual violence would get rid of the shame by marrying her rapist.

This list shows how the “what we used to do” game is dangerous but helpful. It takes us back to dark times, where in the name of opinions, beliefs, religions, and delusions of omnipotence, we have justified genocides, exterminations, abuses, violence, brutalities, and atrocities.

Our species should aim for a process of evolution, not involution. Today, we have scientific and nutritional information explaining what our bodies need and do not need in great detail. We know the exact environmental impact of our food choices and acknowledge the horror of slaughterhouses and intensive livestock farms. Yet, our society struggles to develop a careful sensitivity to the issue. I believe the center of our concern, as social scientists and, above all, as human beings, lies precisely in this terror of looking beyond the curtain, the sliding drape that divides the theater stage from the auditorium and the audience.

Looking beyond would require us to make the cognitive effort to recognize the blindness that has overwhelmed us all our lives, transform ourselves from mere spectators to political actors, and be the driving force of change. We are no longer victims and unwilling executioners of a too-powerful system. Instead, we are policymakers.

Universities today talk copiously about sustainable cities and mobility and the role of urban planning, engineering, and technology in reducing our environmental footprint. Yet, there needs to be more and more accurate mention of food.

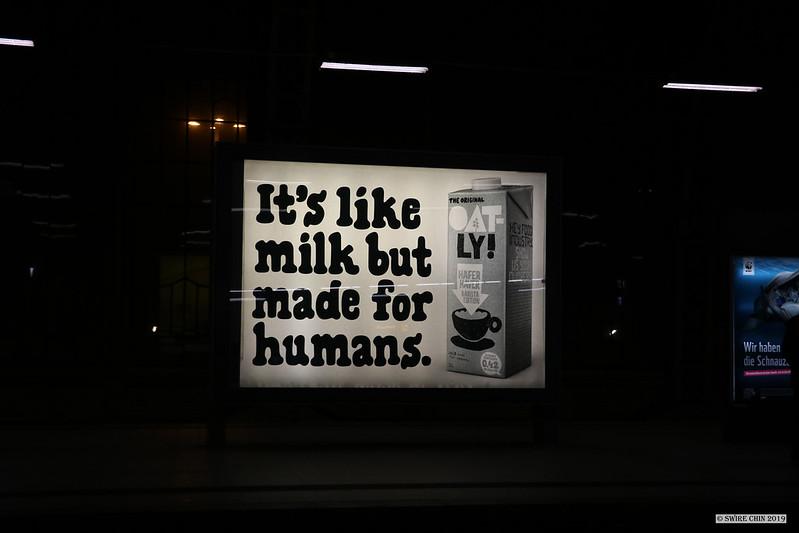

Why do we eat the way we do? Does it have to do with what we need nutritionally or with an idea of nutrition firmly imprinted within us? Do we really know where calcium comes from? Why are we the only species in the world that drinks milk meant for calves as adults? If we need milk so badly, why doesn’t our mother continue to produce it for a lifetime? Where and how do we get iron? I often hear that vegans, in the common imagination, are pale, have nutritional deficiencies, and suffer from various diseases due to their diet. Likewise, do we know the impact of processed meat and dairy on our health?

It is time for action and not for redundant words. Yet, they become crucial because we used them for so long to create a dangerous gap between scientific truth and imagination/fake news. For this very reason, I do believe it has a pivotal role the reminder that tofu is not the cause of Amazon’s deforestation, as 80% of the soybeans grown become animal feed (scientific fact), despite being the favorite argument (fake news) of those who stonewall different dietary habits, namely plant-based options.

The goal of this article is not to convert people to veganism. Instead, we have to ensure equal access to scientifically accurate information about the impact of the food industry on the Planet, on human beings, and on the animals involved in the process, seen as mere products, and not as sentient beings.

Academics are still not playing the pivotal role they should be playing, remaining in the background and still hooked on a reference system that is no longer observable as a model. Perhaps it would be correct to keep Bauman’s view in mind. The widespread diffusion of mechanized and standardized food production processes makes it possible for a highly specialized, efficient, dehumanizing, and timely industry of death. In the age of rationality, what could be more frightening?

“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”

(Animal Farm, G. Orwell, 1945)

Nicoletta Moschini is a visiting research student at the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon (ICS-ULisboa). She is pursuing a MA double degree in Sociology and Social Research from Università di Bologna and Bielefeld Universitaat. Her research interests focus on the social and environmental impact of livestock farms. She is a human and animal rights activist (Amnesty International – Italy; Esseri Animali). Email: nicolettamoschini@edu.ulisboa.pt